Two heads are better than one. At least that’s what we’ve been led to believe. Too bad it’s not always true.

Remember when the game show, Who Wants to be a Millionaire? was all the rage? The show featured what it called lifelines, basically three chances to get help when the contestant was stuck on a question. One option was to ask the audience. When the contestant took this option, the question would be put to the audience by electronic polling. The contestant would see what percent of the audience voted for each of the four possible answers. In theory, the answer with the highest audience response would be the correct answer.

The audience knew its stuff. A quick web search indicates it recommended the correct answer more than 90 percent of the time. Here’s the problem, sometimes a majority got it wrong. And even when the answer with the most votes was correct, there were always plenty of incorrect answers in the audience.

The audience knew its stuff. A quick web search indicates it recommended the correct answer more than 90 percent of the time. Here’s the problem, sometimes a majority got it wrong. And even when the answer with the most votes was correct, there were always plenty of incorrect answers in the audience.

One reason the audience was able to do well is that they all voted independently. In other words, there wasn’t a discussion before taking the vote. Also, the votes were anonymous. This mattered, because the people who were clueless weren’t able to lead astray those who knew the right answer. In meetings, that’s rarely the case. When people interact, they tend to diminish one another’s ability to get it right.

There are many thinking errors that affect the quality of our decisions. I call them decision traps. Traps catch us, because they are hidden and unexpected. If we know they exist, we can be on the lookout for them.

My goal for this article is that you become alert to them and warn meeting attendees when they are getting too close to one.

Here are eight that will mess up your group if you don’t see them coming.

Anchoring

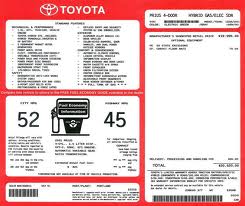

Our brains place more importance on the first information they receive. This is why first impressions are so hard to erase. It’s also the reason there’s a sticker price on a new car that neither you nor the dealer expect that you’ll pay. The price represents an anchor, one that’s on the high side. The dealer wants to start high and work down from there, rather than starting low and working up. As you might guess, this gives the dealer a negotiating advantage.

Our brains place more importance on the first information they receive. This is why first impressions are so hard to erase. It’s also the reason there’s a sticker price on a new car that neither you nor the dealer expect that you’ll pay. The price represents an anchor, one that’s on the high side. The dealer wants to start high and work down from there, rather than starting low and working up. As you might guess, this gives the dealer a negotiating advantage.

In a meeting, this trap may be unintentionally sprung when one person offers the first opinion about what happened or what should be done. If the person makes his statement with conviction and strength, it ends up representing a reasonable starting point. The problem is that it may be completely wrong or unreasonable. Even if the group moves away from that starting position, the anchor may be so strong that the final decision is closer to it than it should have been.

As a meeting hero, help the group be wary of anchors. When a position is forcefully stated, remind them that they’ve heard only one idea so far. There are likely others, and it is important to identify those before making any decision. Another response, especially when opinions are stated as facts, is to ask the person to back up her position with data that proves the assertion.

Know that some people may purposely use anchoring. They take an extreme position they know isn’t likely to win people’s agreement, but advocate for it to pull people in the direction they want them to go. This won’t be a problem in your meetings, because you’re going to catch and stop it. Be alert.

Confirming

Human beings want to be right. We especially want to be right about our core beliefs. Can you imagine going through life wondering whether or not the things you believe to be true actually are? That would be a tough world in which to live.

So here’s what we do to keep ourselves from going crazy. We pay way more attention to data that supports our point of view and discount information that opposes it.

In meetings, this trap affects decisions when some of the most outspoken participants ignore key data because of their strongly held views or when the group has some shared belief.

Take the following example. Imagine a group of help-desk technicians getting together because their director got the results of a customer survey. The group scored poorly. The techs’ prevailing belief is that users are stupid. They tell stories about all the stupid things users have said and done during the past couple of months. As a result, they decide the problems can only be resolved by better educating users. They ignore their own contribution to the problem. That would be a mistake and a fine example of the confirming trap in action.

Here’s how to avoid this trap. Figure out what the underlying beliefs are and ask the following questions:

- What if the belief isn’t true?

- What’s an opinion that counters our belief, just so we can consider it?

Stay vigilant for leading questions that would cause people to answer a certain way. If you hear one, challenge it. Back to the IT example. Asking, “How do we get customers to stop calling us with stupid questions?” plays right into the confirming trap. Here are some better questions you might ask in response:

- What’s a stupid question?

- What would happen if they stop calling us?

- How might we better handle problems that we hoped customers could have handled themselves?

Justification

Once we have invested money or time in an effort, we’d like to believe that doing so made sense. When faced with a decision for which one answer would force us to admit that a previous decision was a poor one, most people will avoid making it. This is the justification trap.

When people strongly advocate for staying the course, an alarm should sound in your head. The question to ask the group and keep asking until it has been honestly answered is, “If we didn’t consider what’s already happened and started with a blank piece of paper; would we still make this choice?”

Accountants use the term sunk cost to describe a cost that has already been incurred and thus cannot be recovered. When making decisions, rational players will only consider the future costs. The sunk costs are irrelevant. Unfortunately, the people in your meetings aren’t completely rational. If they had anything to do with the sunk costs, they will want to justify their previous decision by continuing on the same path. They are fearful that if they chart a different course, it will be an admission of their poor decision. Most individuals I know aren’t great at admitting mistakes. Groups are even worse.

Here’s an example that will help you see this concept in action. In my city, we restriped an avenue to add something called advisory bike lanes on both sides of the road. If you are curious about what that means, search the web. You’ll find it. For our purposes, all you need to know is that drivers were confused. There were howls of outrage that these new lanes were creating a dangerous situation for both drivers and bicyclists.

Some residents asked the city council to remove the lanes and return the striping to its original configuration. One argument against changing things back was that the city had already spent a quarter million dollars. Returning the road to the way it was would mean all that money had been wasted.

If the city council kept the lanes because of the money it had already spent, the justification trap created a poor decision. A group that avoids this trap will ignore those costs and debate whether or not to keep the lanes based on other factors, such as drivers’ ability to learn the new rules, safety for cyclists and drivers, and desire to give the new lanes a chance to work.

If you were to lead a meeting to make this decision, and the group spends a lot of time talking about what they’ve already done, ask the following questions to help extricate them from the justification trap:

- What are the future costs we might incur if a serious accident occurs and the city is sued?

- What’s the impact of keeping the stripes, if they are making things worse than they were before?

Your heroic goal is to keep people focused on the future, rather than on the past. It won’t be easy, but I know you can do it.

Safety

We have a bias for padding our thinking “just to be on the safe side.” If you want to see this in action, think about packing your suitcase for a vacation. Compare the number of times you bring more than you need versus the times you don’t pack enough. I don’t know if I’ve ever met anyone who says that he or she didn’t bring enough clothes.

Press them on why they over-packed, and they’ll say, “I might need it.” They’ll also argue there’s no downside to bringing stuff. I’d argue that there is. The person has to schlep heavier bags. If it creates an extra bag or one that exceeds airline weight limits, there will be extra charges. Depending on the number of travelers, you may need a larger and more expensive rental car to accommodate the extra luggage.

There is almost always padding in group decisions. It’s easy to make a case for doing so. Unfortunately, nobody argues against it. That’s where you come in. Your job is to challenge groups to trim their decisions. Help them consider the costs associated with their desire to be on the safe side.

It’s like buying insurance. You can insure something to the point where there is virtually no risk. The problem is that it will cost too much. Most people make those trade-offs between the risk and the cost. The people in your meeting need to do the same.

The other approach is to help them see the benefits of removing the padding. Let’s say your group is deciding on due dates for major project milestones. The members consider every possible thing that could go wrong or create delays. As a result, the project completion time is forecast to be 18 months.

You know the project sponsors want the work completed in less than a year. This is when you start to pitch the benefits of tightening the estimates in order to shorten the total time. You argue a shorter timeline will keep people engaged. What else would you add to a list of benefits for moving more quickly?

Familiarity

We have a bias for the status quo. Even if the current situation isn’t working, at least it’s well-known and predictable. It’s often not possible to know for sure whether something new will work. Getting people to change is a lot of work. They prefer sticking with what is.

Let’s say you are at a critical decision point in your meeting. The options are turn left, turn right, or continue on the current path. Heroes know that the turns will generate more resistance than continuing straight. Without your intervention, the group will likely convince itself to stick with the status quo. Now that may be the right answer, and hopefully, if it is, the group will choose it. But what if it isn’t? In order for the group to choose to turn, it will need to overcome this trap.

Let’s say you are at a critical decision point in your meeting. The options are turn left, turn right, or continue on the current path. Heroes know that the turns will generate more resistance than continuing straight. Without your intervention, the group will likely convince itself to stick with the status quo. Now that may be the right answer, and hopefully, if it is, the group will choose it. But what if it isn’t? In order for the group to choose to turn, it will need to overcome this trap.

Here’s how you can help. When someone proposes a change from the status quo, the group will normally start evaluating the idea by examining the costs, dangers, and challenges associated with the proposal. That’s fine. The group should identify and consider these. They only represent part of the evaluation process. Here’s the question that typically is not asked, “What are the costs, dangers, and challenges if we stick with the status quo?”

There are times when sticking with the current program makes a lot of sense. We just don’t want a common trap to keep us there because we didn’t thoroughly examine the options.

Overconfidence

Most people think they are better at making predictions than they are. As a result, they go for it based on gut instinct, overlooking important information. The worst of them don’t even know what they don’t know. When they are in your meeting and deliver their predictions as if they are indisputable facts, they sway the group. If the person making the prediction is wrong, the group makes a lousy decision, because it started with faulty information.

To keep your group from falling into this trap, you must constantly push people for evidence to back up their claims. Here are a few of my favorites:

- “How do you know that to be true?”

- “On what evidence have you based your opinions?”

- “Before we move forward, we ought to confirm that information to make sure we don’t decide based on an unproven assumption.”

- “Let’s check the data to see if it supports these conclusions.”

Recallability

We give more credibility to events that we can easily remember. This is why people who are afraid of flying usually don’t have similar fears when they travel by car. Statistically, people are more likely to be injured or killed in an automobile accident than they are in a plane crash, but our brains tell us just the opposite. It’s because when a major plane accident happens, it is top news for days. Impressions of the accident are permanently etched into our memories. Meanwhile people die in car accidents every single day, and we don’t hear anything about them.

The way this plays out in a meeting is when someone shares a memorable anecdote. People refer to one or two cases where something occurred that supports their point of view. And while those cases may be true, the group acts as if they are a good representation of what is happening. They then make misguided decisions based on those beliefs.

Take the example of a group of managers discussing an employee who was caught stealing from the company. When the facts come out, it turns out to be quite a brazen criminal act, not one that people will easily forget. Now the decision turns to what should be done about it. Here’s where the trap creates problems. The group reacts to this isolated incident as if it is a widespread problem. They decide to implement strict new security procedures. This inadvertently communicates to employees that managers don’t trust them.

If it is a widespread problem, perhaps they made the right decision. But what if it is not? In this case, your job is to get them thinking more clearly. Here are questions I’d ask to help create some perspective:

- “How widespread is the problem?”

- “What’s the impact of what we are proposing and does it fit with what we believe is happening?

- “Before deciding anything, shouldn’t we first try to determine if this is one case or if it represents a broader problem?”

- “If we treat it as a broad problem, what will be the impact on our workforce?”

Here’s another example. A group of executives discusses the performance of high potential managers within their company. Due to this trap, any manager who had a highly visible mistake in the last month is going to suffer. A manager who just did something amazing will likely be graded higher. It’s possible that the first person is consistently amazing, except for his recent mistake. The latter person is consistently a decent performer, but rarely performs at a level to match her most recent success.

In cases like this, you can help by asking the decision makers to look at the record for longer time periods. Make sure they gather the pertinent facts and don’t rely solely on memories. Doing so leads to poor decisions.

Groupthink

The most famous group decision trap is something commonly referred to as groupthink. This occurs when the need to get along overpowers the need to get it right. It can be made worse when any of the following conditions are present:

- There’s a strong and persuasive leader. Nobody wants to challenge this person.

- There’s a high level of group cohesiveness. Nobody wants to challenge another team member.

- Intense pressure from outside the group creates an us versus them People believe they must stay united to keep from being hurt.

Groupthink also occurs when meeting participants don’t know one another, and everyone wants to make a good first impression. They don’t want to assert their opinions too strongly for fear of looking like a jerk. Groups eventually move from that phase into one where individuals do take positions that may be counter to what others think. That’s what you want.

In other groups, people may all be friends and perceived to be on the same side of the issues. When they meet, it’s hard to be the one who breaks from the group norm. I happen to live in a state that holds caucuses. These are meetings of people from the same neighborhood who all belong to the same political party. One common caucus activity is to rally support for a particular issue or position that someone wants to make part of the state party’s platform.

It takes a brave soul to suggest something that may rub against a long-held party position. My guess is that many won’t do it. Maybe they should. It could be the start of a change that would be good for the party’s long-term health. When groupthink occurs, people will not offer their suggestions, because they want to be team players. If they do, a majority will immediately snuff it out with some dismissive argument, such as, “That’s not what we believe as members of this party.”

When groupthink grips a meeting, you can expect some stupid decisions. The meeting will also lack innovation, because the status quo usually prevails. Here’s what you can do. Encourage people to challenge one another. If they don’t do it themselves, create an opposing position and ask people to make a case for it. Ask someone to be the devil’s advocate. I have a variety of common lines I use. Here are some you might try:

- “So far we have only one position as a group. Seems to me we should consider a couple of others for the sake of thoroughness.”

- “I’m concerned that people aren’t saying what they are thinking. What’s not being said that should be?”

- “Okay, I hear that you all think we ought to pursue this plan. For argument’s sake, let’s take a minute or two and imagine what opponents of this idea will say when we present it to them.”

Act Heroically

Making decisions as a group is challenging work. Groups rarely make perfect decisions. Some make more than their fair share of bad ones. In those cases, it’s probably the result of having fallen into a decision trap. Here are some practice exercises that will help you build the skills you need to keep a group out of these traps:

- Whenever you find yourself with what appears to be a unanimous decision, especially when that much uniformity is unexpected, ask the group to take time to consider choosing another option.

- Get in a habit of challenging assumptions, ask for evidence, and push people to back up their statements with facts.

- Appoint the role of devil’s advocate in your meetings. Tell the person her job is to poke holes, challenge, and offer alternatives. Make sure it’s not always the same person, no matter how good she might be in that role.

This article is an excerpt from my book Meeting Hero: Plan and Lead Engaging, Productive Meetings. Pick up a copy on Amazon.