I watched parts of the trial for former Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin. When it came time for the jury to deliberate, I found myself as interested in how the jury would make its decision as I was in what it would decide. I wondered what jury guidelines they were given.

Jury deliberations are, after all, a meeting. I’m a meeting facilitator and always looking for better ways to run meetings.

When the judge provided the jury with instructions, he gave them pages of information about the charges, the law, and being fair. There was even a caution about implicit bias.

All of that information was important for the jury to understand. Still, I was surprised the Court didn’t give them jury guidelines for how to go about their work. The only process direction was to Pick a foreperson. The judge then outlined a couple duties that person would have. It was pretty minimal.

Every jury has the same basic goals. And while there are likely dozens of different paths for reaching those goals, there are likely some proven techniques for how to get there more quickly and with less hardship for the jury. And yet jury guidelines weren’t part of the instructions.

Perhaps the problem is that what happens in the jury room stays in the jury room. They aren’t supposed to speak about their deliberations. This might be what keeps them from sharing practices that worked.

If I was leading a jury

I’ve never been on a jury, but if that day ever comes, I would volunteer to be foreperson because to me the job is the same as facilitator. And because leading meetings is what I do, even writing a book on meeting facilitation, I would feel like I had a useful skill I could offer my fellow jurors.

When I facilitate a meeting for a client, I get agreement on the goals and then build a plan for how to achieve the goal. In this article I’ve imagined the plan I would suggest to my fellow jurors and then work together to make any adjustments. To illustrate the points, I have used the Chauvin trial as my example.

Pick a foreperson

But before I get ahead of myself, the jury’s first step should be to follow the judges one process suggestion, pick a foreperson. This is how to do it.

- Ask for volunteers and nominations. Some people might want to do it without skills. Others may have skills and not volunteer.

- Let each volunteer or nominee say if they are willing to serve and what skills and approach they would bring to the role. My guess is the position usually isn’t contested, but maybe it should be. A bad foreperson can make the process a lot harder.

- Do a secret written ballot. There’s no sense in causing rifts right out of the gate based on who people voted for.

Once this person is selected, the group should discuss the person’s role. Any authority this person has to guide the jury comes from the jury itself, so it would important to gain clarity and agreement about expectations.

In addition to the specific responsibilities outlined by the Court, this person’s role should include:

- Make process suggestions about how to proceed

- Manage the conversation

- Involve everyone in the process

- Create an environment that is safe and respectful for everyone

Warm-up

Before the jurors dive in and start sharing opinions about the case, they should first take care of some warm-up activities.

Icebreaker

While the jurors likely had some time to connect during breaks, they probably did so in small subsets, maybe even forming cliques. From this point forward, they need to start acting like a 12-person team.

It’s also likely that they are nervous. They are about to undertake a difficult task with serious consequences. Most probably have never been a juror before and are apprehensive about what’s about to happen. Some members of the jury might not be comfortable expressing themselves in a group of 12.

Use an icebreaker to help them prepare for their task and ease them into their work. This can be as simple as doing introductions. Here’s what I would invite them to share about themselves:

- Name

- What they do for fun

- How they felt when they got a summons for jury duty

- How they felt when they got selected

- How they feel right now at the beginning of deliberations

- Any hope for how the jury would work together

The questions should be easy to answer. They also help people relieve some anxiety by naming what they are feeling. It also helps to discover others feel the same.

Goal

Remind the jurors what the goal is. In the Chauvin case their goal was to make a decision on three counts. For each count their choices were guilty or not guilty. In order to deliver either verdict, the decision had to be unanimous.

Ground rules

At this stage it would help to have the group decide on some ground rules, in order to feel safe and be productive in their deliberations. Some of the questions the group should answer include:

- How will we decide what topics to discuss and in what order?

- How will we ensure we stay on one topic at a time?

- How will we ensure we limit our discussion to the evidence presented in the case and leave out our biases and information that wasn’t part of the record?

- How will we ensure everyone has a say?

- How will we maintain a respectful environment?

- How will we make decisions?

- If we are voting, will we use a secret ballot, hand vote or individual voice vote?

- What will we do when we don’t agree?

- What expectations, if any, do we have about opinions being backed up by facts?

- When will we take breaks?

By answering these questions prior to deliberating a point, people tend to be more reasonable than they will be later when they already have a strong position and are in the heat of the debate.

If you’re interested in some suggested all-purpose rules for participants, you might appreciate this article on best practices for meeting participants.

Tackling the Questions

Once the warm-up activities are completed, it’s time to get to work on the task at hand.

Hopefully in creating ground rules, the jury decides to operate under the principle, “Let’s not spend time discussing issues that we already all agree on.”

Do a test vote

To get a sense of where things are at, the first thing to do is a test vote. Maybe everyone’s on the same page, and the jury can make short work of its assignment.

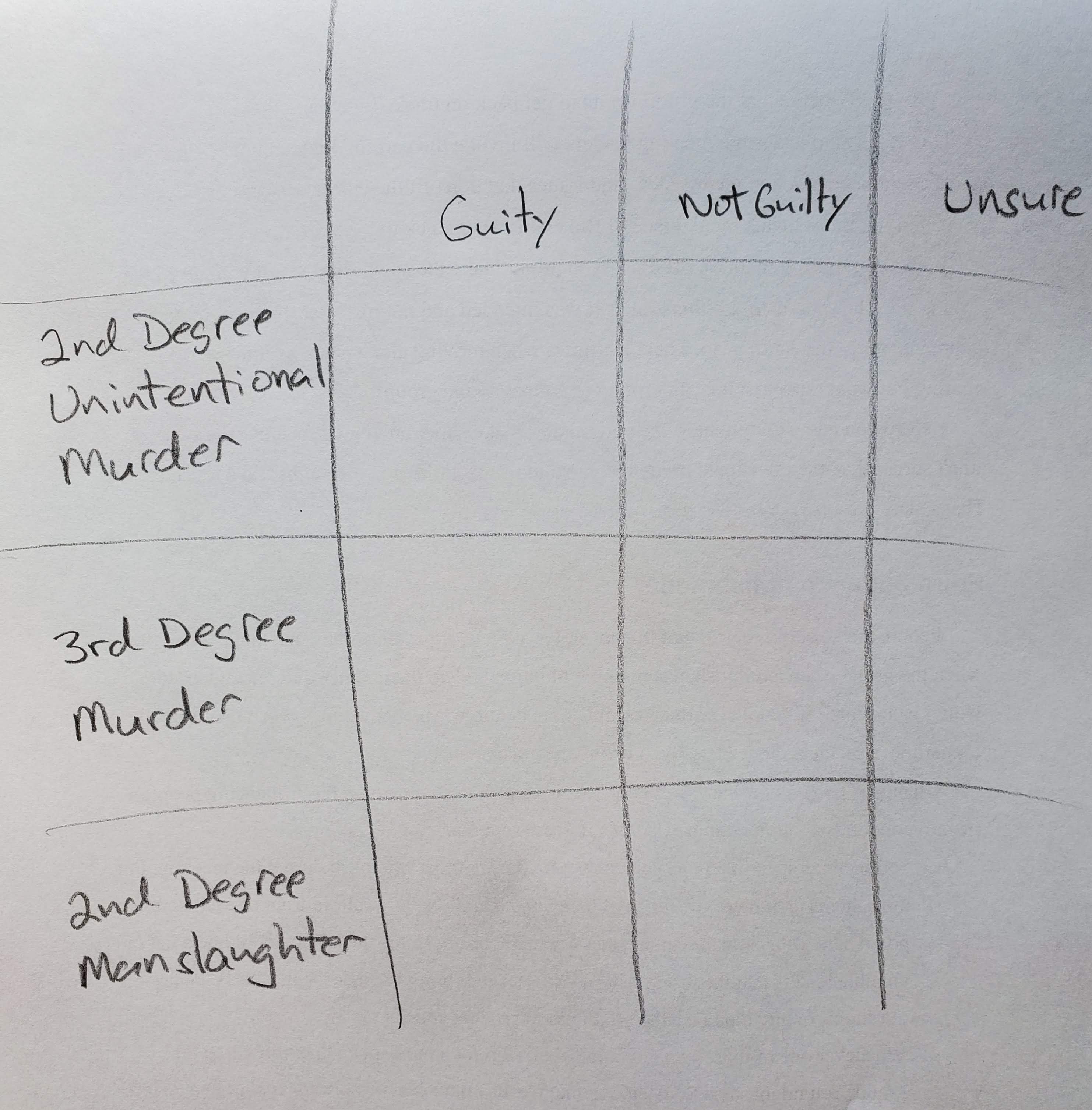

Using a flipchart or white board, I would create the following grid and then ask for a secret written ballot on each of the charges. In the spaces, you would record the vote counts. Again, using the Chauvin case as an example, here’s what the chart would look like.

There are two things the jury learns about itself from this exercise.

- Whether the jury as a whole is strongly leaning one way on any of the charges.

- The amount of uncertainty that exists.

The result of this work would help the group decide what happens next.

Discuss the elements

Assuming none of the charges have unanimous agreement, it’s time to start the hard work. Watching the closing arguments, I learned that each charge had 3-5 elements that must be true in order for the jury to decide the defendant is guilty of the charge. If any are not true, the jury must acquit the defendant of that charge.

I also learned that some of the elements are common between two or even all three of the charges.

Again, the jury could start with a test vote on a specific element. The choices would be:

- True

- False

- Unsure

Once the vote is taken, the jury should start deliberating on this element, assuming complete agreement isn’t present on the test vote.

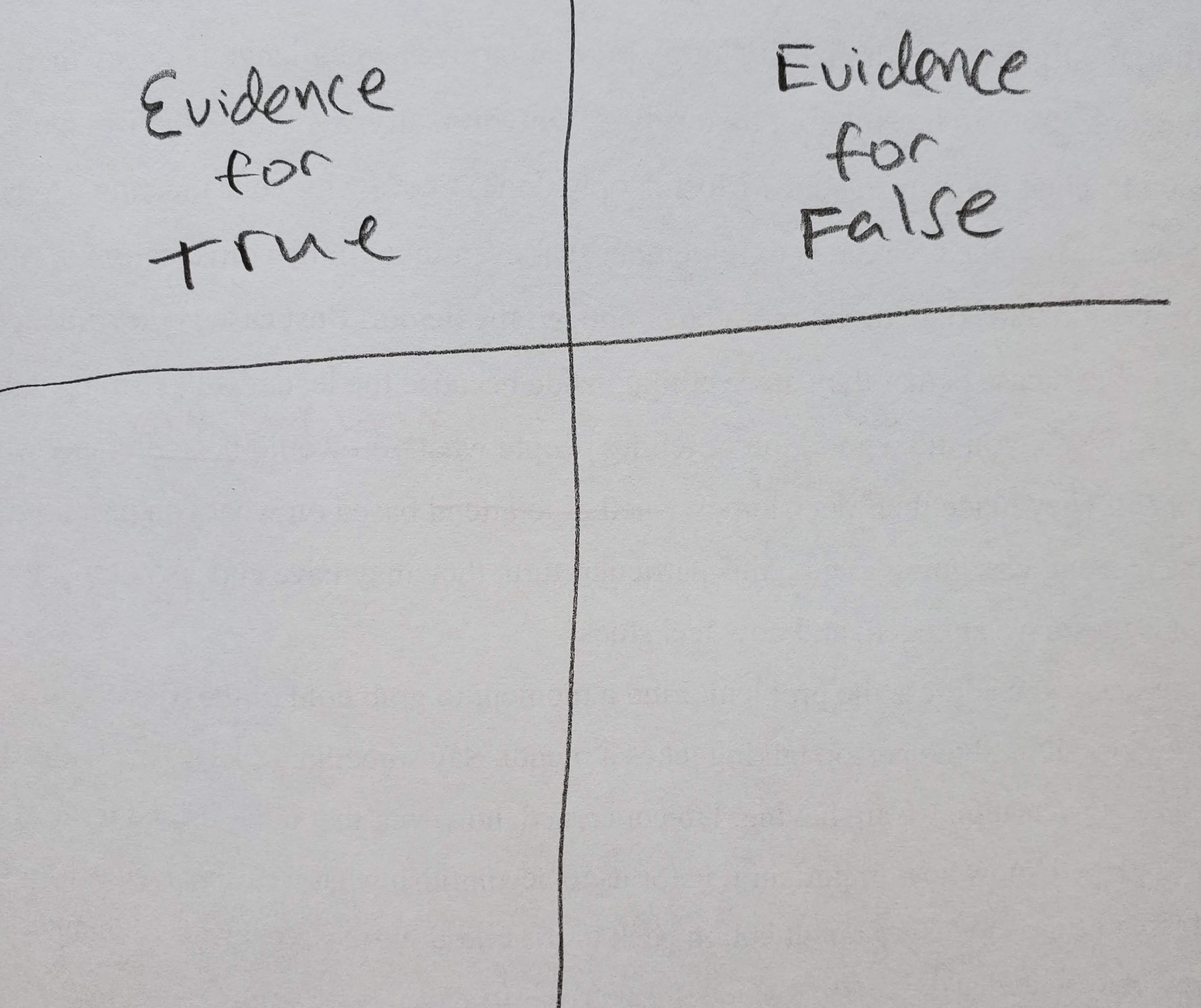

To help the deliberations, I’d again use a flipchart or whiteboard and create the following chart.

Instead of having each person say whether they think it’s true or false, ask everyone to contribute to filling out both sides of the chart. This helps people work together as they examine the evidence and not just be supporting their own position.

Once the chart is completed, the group could discuss whether any of the evidence should be given more weight and why. This might even involve using some numerical system for rating importance.

After that discussion, it would be worth asking, “Based on the evidence list and and our discussion of it, who would change their vote?” A simple show of hands would be good at this point. If some hands go up, do another vote on whether each person thinks the element is true, false or if they are still unsure.

For this vote, ask people to state their opinion for the group. Starting with anyone who is still unsure, ask them to say more about why they are unsure and what would help them decide. As a group, reexamine the evidence to see if you can help those jurors who are unsure reach a decision on that element.

Let’s say, through this process, those who were unsure can now cast a vote for true or false. Then what?

This is when ground rules come into play. Remember that question I suggested the group answer before getting to this point, “What do we do when we don’t agree?” I’d offer several reasonable options:

- We keep talking until we do find agreement.

- We immediately acknowledge we don’t have agreement and find the defendant not guilty on any charge that requires that particular element.

- We all agree to support any majority opinion. In this case that would mean 7 of 12 votes gets the support of everyone.

- We all agree to support a pre-defined “super-majority” opinion. An example would be if 3/4 of us see it one way, we all agree to support it. That would mean 9 votes on an element leads to a decision for that element.

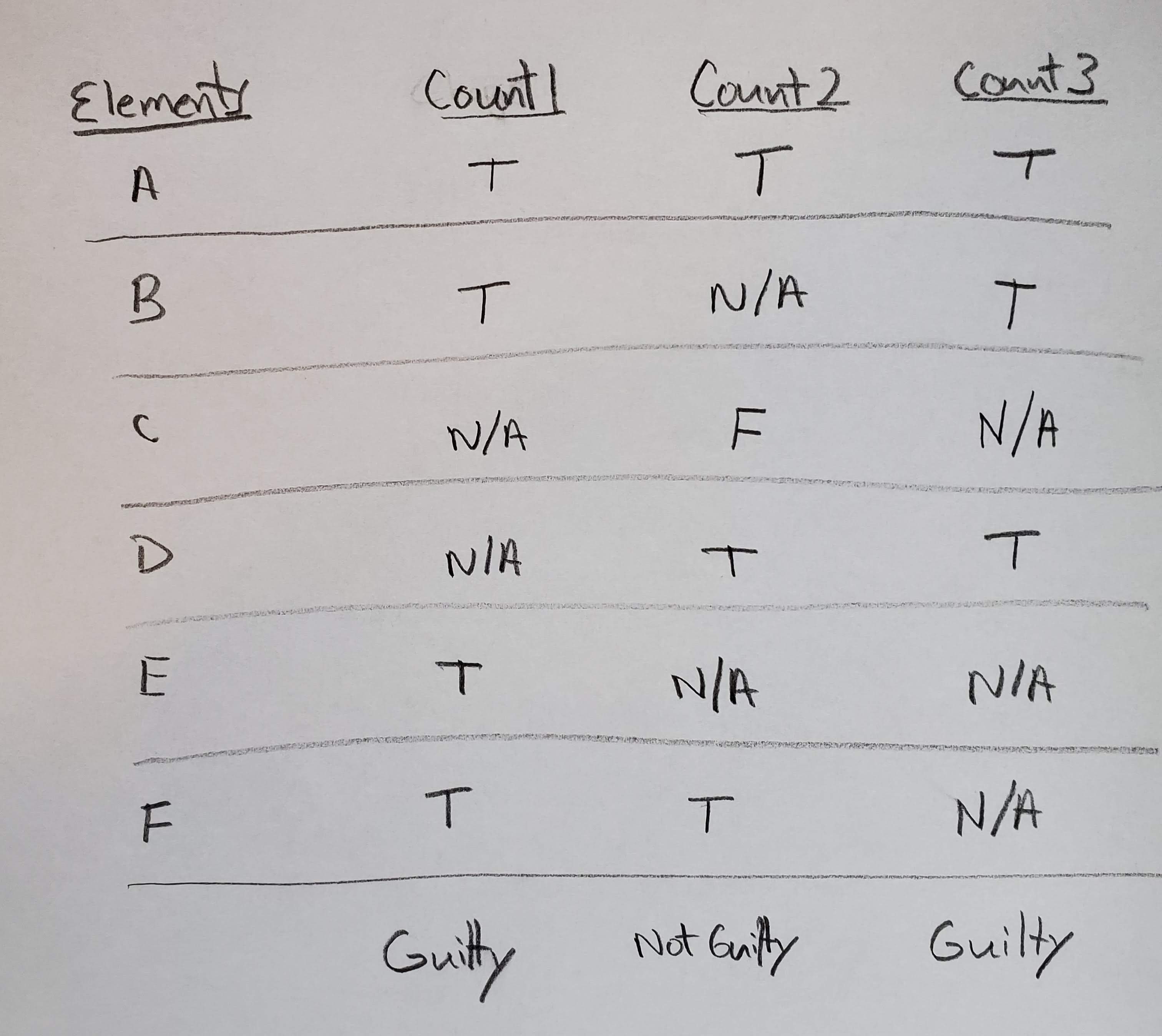

Once the element has been decided as true or false, the jury should note its decision for any charge that requires that element. These decisions could be posted on one chart that tracks all the jury’s key decisions.

On this chart, they could list the collective elements for all charges along the left-most column. Next they should block out any charges the element isn’t required for. A simple N/A or a big X would do the trick. Note that if an element is true or false for one count it should be same for all other counts that require it.

If the jury decides an element is not true, it means that the defendant must be found not guilty on any charge that requires that element.

Suppose for example element A was false. Because it is an element of each count, the defendant would be found not guilty of all counts, and the jury would be finished with its work.

On the other hand if element E was false, it would only affect count 1. All other elements would still need to be decided upon in order to reach a decision on counts 2 and 3.

Assuming the decision on an element doesn’t remove all charges from any further consideration, the jury would repeat the process for another element that is still required for one of the other charges.

It would be best for the jury to debate elements that apply to the most counts first because if they find one to be false, it would help them more quickly arrive at their overall goal of making a decision on all three counts.

Confirmation

When the chart is complete, the verdict on each count should be obvious. Due to the gravity of the decision, it might be smart for the jury members to be given one more opportunity to change their minds on any of decision they made with regard to specific elements.

It’s possible that a person may have had some new insight about a particular element when participating in a discussion about the evidence on another element. The decision rules that the group adopted will hopefully still be followed, but let’s say the jury agreed to the 3/4 rule, but now a person’s changed vote means there are no longer 3/4 in agreement.

If that happens, it would be helpful to have the person who changed their mind explain their thinking, reopen the discussion about the evidence the jury has already discussed and also decide if any additional evidence should be brought into the discussion.

While this might be frustrating to reopen the discussion, it seems a prudent check to make sure the jury gets it right.

Foreperson tips

This person’s job is to help keep the jury on track and moving towards a decision. Some actions that will help is when this person…

- Invites people into the discussion who aren’t saying much. You might be able to do so with your body language.

- Watches body language for agreement or disagreement and responds to it as appropriate.

- Addresses disrespectful comments to enforce the group’s ground rules.

- Reinforces helpful behavior.

- Allows people to change their mind.

- Keeps the discussion focused on one question at a time.

- Reserves own opinions when they won’t make a difference on the final outcome.

Tough job

Juries have a tough job. They need to remember all the evidence. They need to learn about and understand lots of complicated issues. They need to address their own biases. They need stamina to sit through long proceedings. They need courage to do what they believe to be right. They have to work with a bunch of people and didn’t have a say in who they would be.

Telling the jury to go make a decision without giving them some jury guidelines seems like a missed opportunity. They wouldn’t need to follow them if they thought they had a better plan, but my guess is most would appreciate a roadmap for how to do their work. At the very least it gives them a starting point.